By Hafeez Dossa, BSc | Peer Reviewed by Dr. Jessica Otte, MD, CCFP, FCFP

Abstract

Objective: To review the use of tramadol in a long-term care (LTC) facility setting. Based on recent literature, tramadol does not have a better safety or efficacy profile in pain management than alternative analgesics, has more problematic interactions, and comes at a higher cost. Through a pharmacist-led intervention at more than 20 LTC facilities across Vancouver Island, we aimed to re-evaluate the appropriateness of tramadol therapy across all patients.

Methods: This nine-month prospective quality improvement intervention looked at all LTC residents serviced by the pharmacy (approximately 2,000) who had a prescription for tramadol containing medications (tramadol or tramadol-acetaminophen, e.g. Tramacet). Over six months, through medication reviews, care conferences, or individual letters faxed to prescribers, recommendations were made for stopping or switching to alternative analgesic medications. Changes were processed by the pharmacy team as prescribers agreed or disagreed with our recommendations, and results were collected after the six-month mark. A follow up report was generated three months later to identify the durability of recommendations beyond cessation of the intervention (i.e. to see if patients remained off tramadol, or if tramadol was restarted). Total medication costs were also assessed for each resident who had tramadol on their medication list at the start and end of this initiative.

Results: 83 patients were identified that had a prescription for tramadol at month zero. After accounting for residents who were either discharged or passed away during the study period of nine months, 57 remained eligible for follow up. Of these 57 patients, 40 (70 per cent) were no longer using tramadol (12 completely discontinued and did not change to an alternative pain medication, while the other 28 switched to a more appropriate analgesic). 17 (30 per cent) remained on tramadol. The average monthly spend for each patient on tramadol prior to intervention was reduced by approximately $40 per month (or approximately $480 annually). Total cost savings achieved across all residents, on an estimated monthly basis, was approximately $1,550/month (or approximately $18,600 annually).

Conclusion: A pharmacist-led intervention in a long-term care setting can dramatically reduce the inappropriate use of tramadol. This allows for a reduction in unnecessary drug costs, may be associated with reduced drug interactions, reduces pharmacy dispensing, and reduces nursing administration workload, without negatively impacting pain management. Clear communication and collaborative care are factors that facilitated the reduction in inappropriate and unnecessary use of tramadol. These findings can inspire other pharmacists and health care professionals within an interdisciplinary setting to consistently re-assess the appropriateness of all medications, including tramadol.

(Left to right) Pharmacists Irene Yan and Gilbert Qin, pharmacy manager Hafeez Dossa, pharmacy technicians Caitlyn Ninatti, and Maran Kokoszka.

Let’s talk about tramadol.

According to data from PharmaNet in 2020, almost 150,000 British Columbians received a prescription for tramadol (any formulation). From its introduction to Canada in 2005 until very recently, tramadol was not considered a narcotic medication. But in March of 2022, tramadol was added to Schedule 1 of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.

What does this mean to me as a patient who’s looking for a solution for acute or chronic pain? As health-care professionals, how do we really feel about tramadol? Let’s review.

When considering medications for pain management, we typically would consider the following stepwise approach:

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- NSAIDs (Ibuprofen/Advil, Naproxen/Aleve, Diclofenac/Voltaren)

- ????

The “????” is based on a few factors. Does the patient have nerve-related pain, perhaps from complications associated with diabetes? Let’s explore gabapentin/pregabalin. Is there a potential case to consider sciatica or lower back pain? Does the patient also have depression? Maybe duloxetine or a tricyclic antidepressant would be the answer. None of the above? Are we comfortable enough to look at cannabinoids, such as nabilone or medicinal cannabis? Might want to consider referring this to a specialist.

But the patient is looking for an answer, now. Hydromorphone or morphine? Opioids sound scary, given their abuse potential, the potential need for a triplicate prescription and the risk of overdose; not to mention the stigma associated with narcotic medications and the fentanyl crisis.

Then there’s tramadol. Marketed as “not quite an opioid,” but a step up from acetaminophen and NSAIDs. Tramadol is often considered a “safer” opioid based on its pharmacology and seen as a drug with not as high of an abuse potential, and risk for overdose, compared to opioids. And until 2022, in Canada, this wasn’t considered a narcotic medication. Seems like the logical next step, doesn’t it?

Let’s consider the following when reviewing tramadol:

- A major metabolite of tramadol (M1) does have affinity for opioid receptors. However, its potency for activity on these receptors is around 10 per cent relative to morphine, so in theory, it is not as potent of an opioid, and many would consider this to have a lower risk of abuse potential versus traditional opioids. It also doesn’t sound as scary as morphine, hydromorphone, or fentanyl. Most wouldn’t consider tramadol to be a narcotic medication, until recently.

- Tramadol also has activity on other neurotransmitters, including serotonin and norepinephrine. Similar to some antidepressants (e.g. venlafaxine), tramadol reduces the re-uptake of these chemicals, which may help with an overall reduction in pain and improvement in mood.

Based on the above information, tramadol sounds pretty cool! Why would someone who has not found success with other OTC and prescription pain medications not try tramadol?

Let’s also consider the following:

- Tramadol is not covered by PharmaCare, is not an LTC Plan B or Palliative Plan P benefit, and is also not available for special authority. This means that unless you have a third-party plan that pays for tramadol, you’ll be paying out of pocket. And tramadol isn’t cheap. If taking Tramacet twice daily, our patients pay approximately $40 per month, or $480 annually. Note that opioids, such as hydromorphone and morphine, are covered by PharmaCare. For LTC residents (PharmaCare Plan B), both are fully covered and would come at no cost to the resident.

- Because of its activity on serotonin and norepinephrine, there is a risk of drug interactions. Many patients in a LTC setting take antidepressants, such as escitalopram or venlafaxine, and side effects of using both at the same time include an increased risk of falls, serotonin toxicity, and insomnia. Although opioids such as hydromorphone and morphine do have adverse effects, they do not carry with them the same risk of interactions as tramadol, as they act only on opioid receptors.

- There is evidence that suggests tramadol may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, which is especially concerning for elderly patients.

- It is debatable whether or not tramadol is as effective when compared to opioid pain medications, such as hydromorphone and morphine. Recent literature, such as a large Cochrane review on tramadol for osteoarthritis also suggests that tramadol may not even be as effective as traditional OTC pain medications such as ibuprofen.

If opioids are potentially equally or more effective, have less risk of interactions, and are cheaper, why don’t we just use them in the first place? This question prompted me to see what would happen if we started this conversation with the prescribers of our patients taking tramadol.

At CareRx Parksville, we service approximately 2,000 patients who reside in LTC and Assisted Living facilities across Vancouver Island. We have the opportunity to collaborate directly with physicians and nurses through care conferences, medication reviews, and medication reconciliations during transitions into care, which enables us to engage in meaningful conversations on whether drug therapy is appropriate or not.

In November 2022, we ran a report of all patients taking tramadol containing medications (tramadol, Tramacet), and found that 83 had an active prescription. We made recommendations for each individual patient for either of the following:

- An alternative pain medication, such as hydromorphone (if pain was classified as severe and requiring opioids) or acetaminophen (if pain was classified as non-severe).

- A reduced dose, if it was determined that tramadol was an appropriate pain medication.

- Changing to a PRN dosing administration, to determine if regular dosing was necessary in the first place.

- A discontinuation of tramadol altogether, if there were no complaints of pain based on feedback from family/nursing staff.

- Continuing the previous dose of tramadol, if it was determined there was an appropriate reason.

We made these recommendations to the prescriber, following a consultation with the patient’s nurse, family, and/or care aides involved in the patient’s care.

After six months, all recommendations had been made, and changes to patient’s medications profile had been processed by the pharmacy. We waited another three months before compiling the final statistics, to account for any patients who may have reverted back to their previous regimen of tramadol due to an increase in pain following intervention. At the nine-month mark, in June 2023, we eliminated those who were either discharged from the facility, or passed away during the study period, which left us with 57 patients.

Here’s what we found:

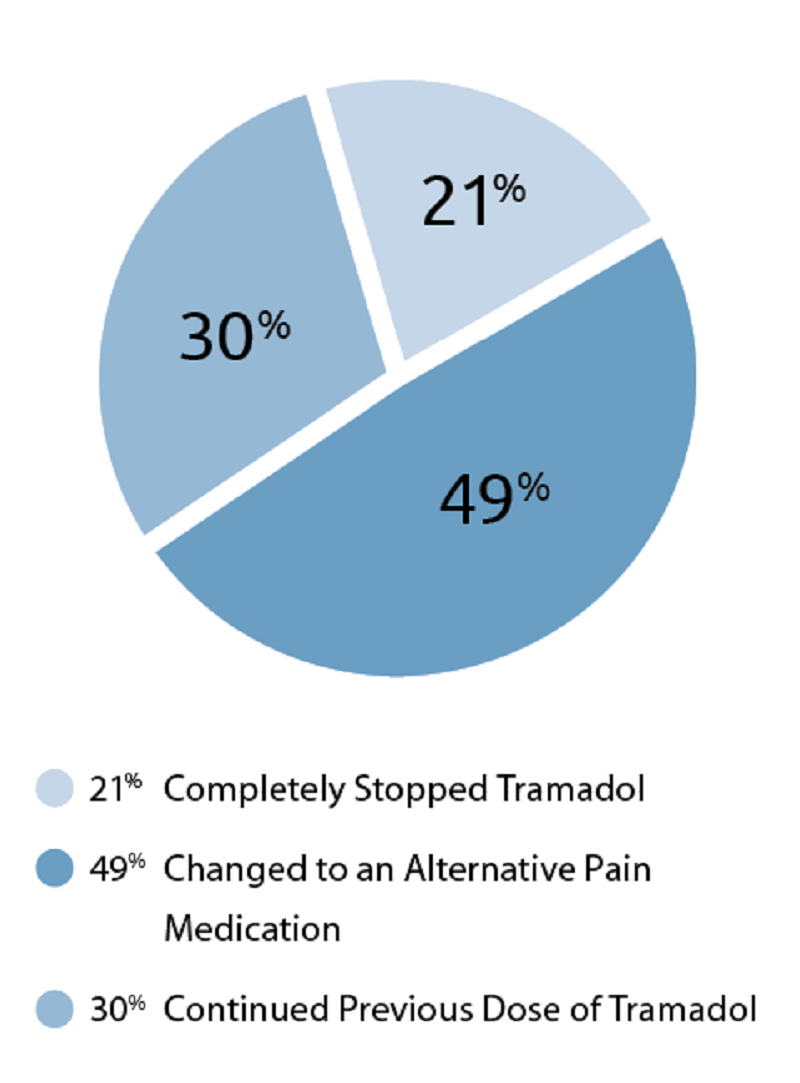

- 40 patients (70 per cent) completely stopped using tramadol.

- 12 patients (21 per cent) did not switch to an alternative pain medication (i.e. did not need medication for pain management n the first place).

- 28 patients (49 per cent) switched to an alternative pain medication, such as acetaminophen, hydromorphone, or fentanyl.

- 17 patients (30 per cent) remained on their previous dose.

What was the impact of this?

For the patients who stopped taking tramadol, there were no reports of worsening pain.

We reduced the risk of interactions associated with concurrent drug therapy with antidepressant medications, along with a reduced risk of hypoglycemia.

In some cases, we also eased the administration of medication for nursing staff:

- If no alternative medication was prescribed, this would reduce the need for administering a medication (which includes crushing medications in some cases).

- If hydromorphone was selected as the alternative medication (this was the most commonly selected alternative), it is a much smaller tablet, which is much easier to swallow. As mentioned, hydromorphone is fully covered by Pharmacare Plan B for LTC residents, which means the drug is free for these residents.

We achieved significant cost savings. The average patient taking a regular dose of tramadol, without third party coverage, saved approximately $40/month, or $480 annually. On a cumulative basis, this entire project saved the 57 total patients approximately $1,550 monthly, or $18,600 annually.

Let’s review two cases where tramadol was successfully deprescribed:

- Resident A, a 91-year-old female, was taking two tablets of Tramacet twice daily. Following a medication review, it was suggested that the patient switch to hydromorphone 1mg twice daily, as this patient did need medication for management of their pain, but there was no documented reason for Tramacet being preferred over other opioids. There was no reported change in management of pain, and this resulted in a cost savings of approximately $120 per month, or $1440 annually.

- Resident B, an 86-year-old female, was taking one tablet of Tramacet twice daily, and also had an additional dose of one tablet twice daily as needed for pain. During care conference, it was suggested that this patient may benefit from more consistent around the clock pain management with a fentanyl patch, as they had challenges with taking oral medications. Special authority was granted, and this patient was changed to a fentanyl patch (12mcg strength applied every 72 hours), in addition to changing their PRN medication to hydromorphone 1mg three times daily as needed for pain. This change resulted in a cost savings of approximately $50 per month. There was no reported change in pain management, and this resulted in a cost savings of approximately $50 per month, or $600 annually.

Some examples where continuing the previous dose of tramadol was considered appropriate included the following:

- A previous history of opioid addiction with morphine, where tramadol did not have the same level of dependency for the patient.

- Drug allergy to hydromorphone.

- Intolerance to other opioid medications, where drowsiness and an increased risk of falls was cited as a concern, and tramadol did not have the same level of adverse effects for this patient.

If tramadol is not more effective than other opioid medications, is more expensive, and has a higher risk of interactions, why are people still taking it? From my experience working in LTC, there are three reasons why this happens:

- Prescribing inertia. For example, a patient may have been prescribed tramadol 10+ years ago, and found that this was an effective medication to manage their pain. They weren’t taking any interacting antidepressant medications at the time, and had third party coverage so there was no real harm or cost concerns for this patient to take the medication. Another patient may have been discharged from hospital with tramadol, and continued on this medication without questioning its cost and never did have a meaningful conversation with a health-care professional on the risks/benefits of continuing.

- Ease of access and enduring perception that tramadol is not an opioid or is safer than other opioids. Until 2022, tramadol was not considered a narcotic medication. However, despite the recent addition to Schedule I of the Controlled Drug and Substances Act, tramadol still doesn’t require a triplicate prescription as it is not classified as Schedule 1A. The means that a prescriber does not need to apply for a specific prescription pad to write an order for tramadol, but would require this for other opioids such as hydromorphone. For reference, the waiting time for processing an order for a new set of prescription pads is approximately two to three weeks. Although regulations have now changed with regards to tramadol’s classification as a narcotic, these implications affect pharmacy inventory management processes (narcotic counts and drug-keeping records) more than accessibility to prescribers and patients.

- Patient perception. There is a real fear among patients that opioid medications can lead to dependency, have serious side effects, and can cause overdose. Although these points are important to consider, when dosed appropriately and monitored by an interdisciplinary team in a controlled health-care setting such as LTC, opioids can be a safer and equally effective alternative to pain management in comparison with tramadol.

Seated (L-R): Irene Yan, Gilbert Qin, Hafeez Dossa, Ashley Kennedy.

Standing (L-R): Romil Vaya, Cindy Villarico, Maran Kokoszka, Bonnie Stafford, Jaber Khan, Saifullah Khaled, Jeesan Ul-Islam Raktim, Raj Kapadia, MihirShah and Caitlyn Ninatti.

Dr. Jessica Otte, a member of the UBC Therapeutics Initiative, is a physician who does palliative care and is the family physician for some of our LTC patients. She is a strong advocate for the review of tramadol prescribing practices in all clinical settings. She had the following comments in response to the success of this initiative:

“Hafeez has once again demonstrated that combining a bit of determination with starting conversations with prescribers is a successful recipe for reassessing the appropriateness of medications, and that these small interventions have a lasting effect. Having done a Systematic Review on the safety and efficacy of tramadol in my role at the UBC Therapeutics Initiative, I can say there is clearly no safety or efficacy benefit to using tramadol over other opioids and that NSAIDs — when safe for the patient — are likely more effective. The cost of tramadol is high, so if an LTC resident needs opioids, they (and insurers) appreciate deprescribing where possible or lower-cost options when opioids are indicated.

“Tramadol also complicates prescribing as LTC residents might also be prescribed SSRIs, SNRIs, anti-nauseants like metoclopramide, and then be at risk of serotonin toxicity. The fact that tramadol is associated with hypoglycaemia, especially in patients with diabetes, is really under-appreciated. Hypoglycemia can have catastrophic results especially in frail elders in LTC. Fortunately, stopping tramadol or substituting opioids that don’t have these issues, like hydromorphone or morphine, are reasonable options.

“It is great to see that pharmacist-led efforts can help physicians and NPs revisit orders for tramadol or tramadol-acetaminophen and that it really does lead to improvements for patients. Sometimes all it takes is a little nudge to reconsider the prescription, and it seems that “little nudge” has been very impactful.”

Gilbert Qin, pharmacist with CareRx Parksville, understands the impact pharmacists can have on patients in the long-term care sector, and the results of this project highlight the importance of our profession in optimizing medication management:

“As a pharmacist in British Columbia, I recognize our vital role in enhancing public health and ensuring medication safety. Our profession faces significant challenges, including drug shortages, staffing difficulties, and the increasing administrative burdens that can detract from patient care. We remain committed to addressing these issues, such as by reducing unnecessary medications to minimize adverse drug reactions and improve treatment efficacy.”

Qin also feels that this initiative helps support advocacy efforts for the pharmacy profession.

“Additionally, there is a pressing need for increased funding and resources to support pharmacy operations, ensuring we can continue to deliver high quality care. By advocating for better support systems, we aim to fortify our practice and continue to positively impact the health and safety of our communities.”

Ashleigh Wasner is an RN and Executive Director with Eden Gardens, a LTC facility located in Nanaimo. Approximately 140 residents live at Eden Gardens, and four were included in this project. She shared the following comments:

“In my role as the Executive Director at Eden Gardens, I oversee operations at the facility, which includes management of nurses and care staff, building relationships with residents and their families, and maintaining a strong sense of community within our interdisciplinary team. I have an extensive background as a registered nurse, so when patients are admitted to care at Eden Gardens, whether from community, hospital, or another care setting, there have been so many times I’ve questioned whether or not someone needs to be on a certain medication. We work closely with our pharmacy team to review each patient’s drug profile during care conferences and medication reviews, and it’s so great to see the results of this project, especially the cost savings. Many of our residents do not have the capacity to afford such high cost medications, and we appreciate the pharmacy team’s efforts in advocating for our patients. This is only a snapshot of the impact pharmacists have on improving the lives of our residents through reviewing medications — we consistently see reductions in other medication classes including antipsychotics, PPI’s, and antihypertensives — and we commend the initiative taken by the pharmacy team to put this project together, which showcases work that is being done on a consistent basis.”

Many aren’t aware of the role that pharmacists play in LTC, and there are quite a few key players involved behind-the-scenes in making a project like this possible:

- Clinical pharmacists, who are involved on-site at care facilities to engage in medication reviews and care conferences.

- Operations pharmacists, involved in medication reconciliations for patients transitioning into care and verifying the appropriateness of each prescription.

- Registered technicians, involved in final product checks

- Pharmacy assistant staff who type prescriptions, operate packaging machines, prepare medications, and manage inventory processes.

To summarize: These initiatives make a significant impact in minimizing the risk of adverse effects and reducing unnecessary drug spending. As pharmacists, we are the most accessible health care professional, and should always be thinking of whether a drug is necessary or not before dispensing to a patient. I hope that the success of this project showcases to all pharmacists, both in institutionalized settings and in community, how important our role is in the overall health care system, and that we continue to advocate for all patients to ensure safe and effective drug therapy.

Hafeez Dossa is the pharmacy manager for CareRx Parksville, a pharmacy that services approximately 2,000 patients who live in LTC and residential care facilities across Vancouver Island. He is passionate about optimizing medication management, and this project is his second published initiative, the first being in 2020 where more than 50 per cent of patients taking PPIs were successfully deprescribed. A 2017 UBC pharmacy graduate, Hafeez also enjoys playing hockey, pickleball, participating in triathlon events, attending live music shows, and checking out local breweries.

Perry T, editor. Therapeutics Letter. Vancouver (BC): Therapeutics Initiative; 1994-. Letter 131, Tramadol: Where do we go from here? 2021 Jun. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK598531/

The above is an advertisement. For advertising inquiries, please contact michael.mui@bcpharmacy.ca